Should we all just stop eating meat? Meateaters get a bad rap because America’s industrial meat production is resource intensive and has a lousy track record when it comes to the environmental impacts, animal welfare, and the overall health-factor of the end product. But the tide is turning: more sustainable choices spring up each year, and to stop eating meat altogether is to remove our dollars-as-votes from the conversation (this is the same reason I said we should continue to eat wild fish). We have zero power to steer the ship if we’re watching from shore.

Last week, I talked about why GMOs are problematic – mainly because they’re primarily devoted to bolstering the role of commodity crops (corn, soy, wheat, etc.). The domino effect of that type of crop infrastructure is significant. A near majority of those crops are grown as feed for factory farmed livestock, even though they are not biologically appropriate feeds for those animals. This results in bad outcomes pretty much across the board. Let’s outline a few of them – not for guilt, but for evaluating whether this is the path we want to tread moving forward.

So the first part of meat sustainability is a resource question: can this amount of livestock be raised on this amount of land, in perpetuity? When ranches consider the sustainability of their operation, this is the question I hope they focus in on.

The people question of sustainability – will X amount of livestock be able to feed everybody? — opens up a complicated world of ethical and political questions that go well beyond the nuts and bolts of sustainable ranching. For this reason, I’ll leave that gargantuan issue for another day and narrow our scope for today. Can the land support us raising animals on it, and what should our ideal approach look like?

Commodity Crops, Soil Health, and Prairie Land

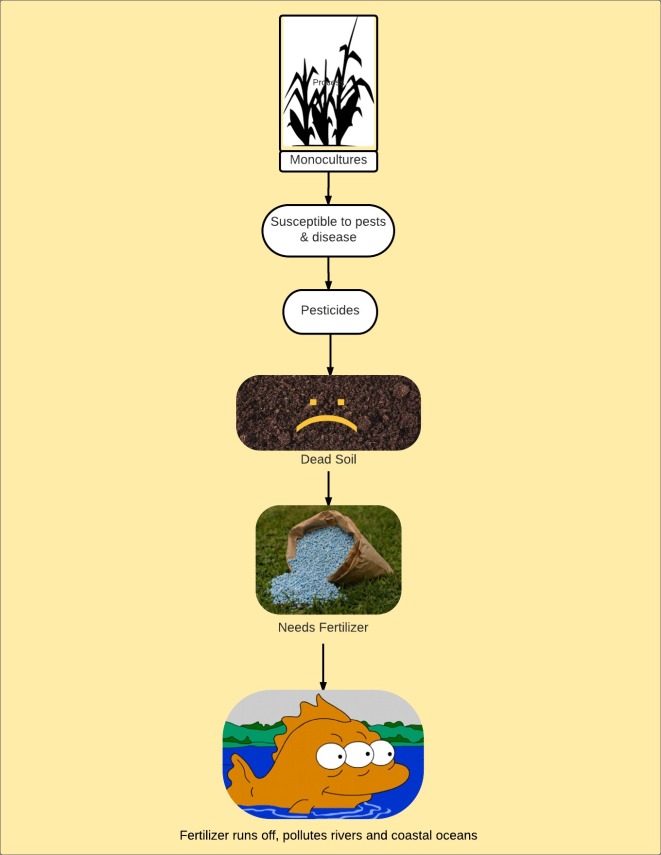

We can’t talk about industrial meat production without talking about the commodity crops that sustain it, and we can’t talk about commodity crops without talking about soil. Because commodity crops are grown in vast monocultures, the overall soil health in our nation’s farmland has been severely depleted in the last half century.

Soil health decreases in monocultures in part because monocultures are more susceptible to pest and disease. Unfortunately, the pesticides we use in response are largely non-selective chemical toxins, so they may kill the pest on the plant, but are also lethal to large numbers of organisms and microorganisms that inhabit the soil. Healthy soil is essential to growing food – we’ve known that for a long time – so it’s no surprise that it’s awfully hard to grow much in dead soil. This has resulted in massive amounts of fertilizer used to keep farmland ‘fertile,’ but also has the unintended side effect of tremendous amounts of fertilizer runoff into streams, rivers, and eventually coastal oceans. The environmental consequences of those behaviors are extensive and will absolutely get their own article here at some point. As these consequences stack up, the “efficiency” of the industrial meat model looks a whole lot more wasteful.

The irony of our current model of meat production is that over time, we have converted millions of acres of prairie land into farmland for commodity crops, most of which we then feed to livestock in concentrated feeding operations. If set loose upon prairie land, ruminant animals like cattle and bison graze upon perennial grasses in a way that sequesters carbon, increases competition and cycling of different grasses and their nutrients, and allows those same plants to develop more significant root systems – all of which diversify and strengthen the structural and microbial integrity of the soil.

In the process, shifting to pasture-raised meat would cause a seismic shift to our nation’s prioritization of commodity crops, pesticide use, soil health, and the presence of pesticides and fertilizers in our aquatic ecosystems and drinking water.

What About Climate Change?

Industrial meat production, and specifically cows, are regularly implicated in being major contributors to the carbon emissions that are causing the planet to warm and the climate to change. This implication is based on two rationales:

1. Concentrated animal farming requires extensive use of fossil fuels

The industrial model of raising animals is built on the premise of producing a lot of animals in a small space – to do that, you need to produce their food somewhere else and then ship it to where your animals are. The cattle themselves are born across various ranches, so they’ll all need to be shipped to the feedlots as well. Once the meat is actually ready for consumption, it must be shipped all over the country and the world to reach the end consumer. Fossil fuels are therefore needed at every step: growing the feed, distributing the feed, transporting the animals to the feedlot, and globally distributing the meat.

In contrast, raising and finishing animals on pasture at a scale that the landscape can support inherently requires a more distributed approach. When ranches are spread out across the country, they are closer to their locally-sourced supplies and their consumers. When that happens, we have a more direct line of communication with the people that produce our food, presumably because a less complicated supply chain is needed to get that meat to a grocery store or a farmers market or a customer’s doorstep.

There’s no question that this method requires fewer fossil fuels. There is less reliance on commodity crops and therefore less shipment of those feeds. The end product also need not travel as long a distance to find the end-consumer. Livestock, be they pigs or cows or chickens or bison or lamb or goats, are able to meet their dietary needs from the surrounding landscape. A rancher may need to supplement their animal’s diet based on what the landscape can provide, but can typically grow that supplementary forage on-site or purchase it from a neighbor. This not only sustains farmers in their community, but holds them accountable for the quality and integrity of what they produce. Ranchers I have spoken to on this topic express enthusiasm for that model, as it supports the biodiversity of their ranch or at least keeps their business expenses circulating within the community. The only barrier they cite is the consumer’s willingness to embrace it.

2. Cattle emit loads of methane (carbon monoxide)

The scientific community as well as advocacy groups within the vegetarian and vegan space have pointed out that that cattle emit loads of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. The argument goes like this: because of the number of cattle that we have in this country, which is currently about 90 million, these methane emissions are quite significant and are directly contributing to the overall carbon emissions that cause global warming.

Those figures are correct, but this argument misses some important historical context: grazing animals already existed on the same land, in great numbers, long before our industrial food system converted the midwest into a patchwork of feedlots and row crops. Formerly, 30-40 million bison roamed these prairies – wild bison are ruminants, which means that they eat grass just like cows do and emit methane, also just like cows do. That number of bison is less, but on the same order of magnitude, as what we currently produce as a nation. So at most, this is not a reason to do away with beef production, but perhaps to directionally scale down our operation closer to a historical baseline of what the landscape can support. In other words, make do with slightly less quantity, but much higher quality meat.

Farming Communities

By design, industrial food production marginalizes communities of small family farms and is the antithesis of the “sustain the farm, sustain the farmer” mantra I talked about a few weeks ago. Instead, the raw efficiency of farming equipment and uniform crop yields are favored at the expense of variety and nutrition. This leaves a smaller and smaller number of farmers producing a greater and greater proportion of the food. By centralizing our food production system, in the process I think we have dramatically and traumatically segregated our rural and urban communities. One of the consequences of doing that, I believe, is the vast cultural and political divide we now see between those communities (Make America Sustainable Again?).

Investing in a more diverse food system, a system of meat production that is less reliant on commodity crops, would require us to spread our meat production across a greater geographic area and a larger number of small producers. One side effect of that change would be that more farming communities would be welcomed back into existence. Those same communities would be closer to the urban and suburban areas that rely on them for food. This would give everyone the opportunity to be more connected to their food and the land it is growing on, but also the community of people that work so hard to produce it. Jobs that had previously been centralized would be redistributed geographically onto small farms, ranches, and micro-supply chains focused on delivering those goods to local, bioregional markets.

What are the best options?

The best changes are the ones we can take action on and can choose consistently. Therefore, it really depends on where you shop, what’s available in your area, and where you are in your journey.

If you’re short on time and want food you know is sustainable without having to pile on the research, try a subscription service like Butcher Box or Vital Choice.

If you want to learn more about where your meat comes from, visit a farmer’s market and ask questions, or a reputable ranch indexed on Eat Wild.

If you just want to pick the most sustainable choice at Trader Joe’s or (insert your favorite local grocery chain here), then stay tuned for some upcoming resources on navigating your local supermarket.

The balance I’ve found over time is buying about 80-90% of my calories from local farms, ranchers, and fishermen via outdoor markets and subscription services like Real Good Fish. My 2017 is all about accessing more wild foods (plant and animal) and learning more of the ins and outs of the domesticated foods I eat, like asking more questions about the diversity of the farms I support are and what eco-restorative practices my ranch of choice pursues.

I certainly understand that other people have different priorities with their families and careers, or live in climates where those choices don’t exist. Not everyone is going to go all the way down this road, and that’s okay. But let’s recognize that the road exists. Those options are there for us to consider, and we bear personal responsibility for owning our choices as sovereign adults and as conscientious omnivores. My approach isn’t perfect, nor will be yours, so let’s not let perfect be the enemy of the good.

As always, I so appreciate your readership of A New Lens. If you liked today’s post, I hope you’ll take a moment to share it on social media or to pass it along to your friends and co-workers.

One of the next aspects of this project that I’ll be working on is a resources section devoted to helpful links, outside content, and new original content focused on actionable information for living more sustainably. This will include information about how to make better food choices, but will also extend to other areas of our lifestyle that impact our well-being and that of our planet and local communities. You’ll see these coming along as soon as this week. To hear more, scroll down and join our email list to receive these updates as they become available.

Excellent article, keep them coming!

LikeLike

Thanks for the feedback Maria, appreciate the support and hope you’ll come on back for next week’s article!

LikeLike